Like millions of people around the world, I got hooked on Game of Thrones because it was great TV. However, unlike millions of people, I discovered it late and thought it was the one of the most racist shows I had ever seen. The picture below has some of the key reasons why.

Game of Thrones (G.O.T.) was the ultimate white liberal fantasy. It was about good white people fighting bad white people with almost no brown people around. The only brown folks were slaves, former slaves or savage warriors, called the Dothraki, who loved violence and looked and sounded like Arabs (the Sinbad movie kind, who were also played by white or kinda white actors).

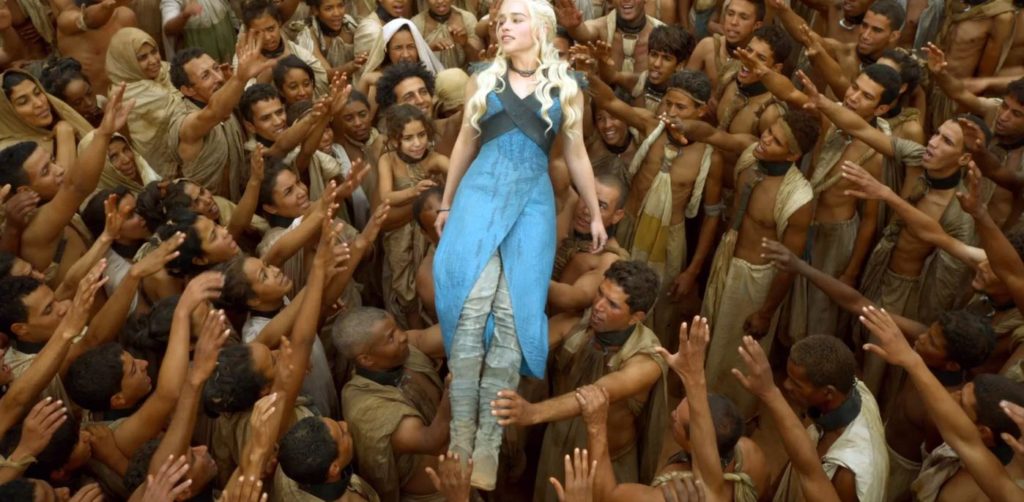

Instead of showing these white folks violently robbing brown folks of their stuff (i.e. what really happened), one of the lead characters, Daenerys Targaryen, was a pretty blond woman who attacked places and freed slaves. After she conquered a place, she would tell the former slaves that they were free to go – but none ever did. In one scene, after she freed the slaves, they hoisted her above their heads like in a mosh pit, and passed her around while calling her “mother” in their native tongue.

The only two brown, main characters are the two in the pic above. Both are former slaves who Daenerys freed. The woman, Missandei, is a translator who becomes Dany’s trusted advisor, but it’s the male character who sets a new racist high for character development.

He is a former slave who was raised as part of a slave army, he now leads. Called the Unsullied, they wear masks so it’s hard to tell what colour they are (but you can judge for yourself from the pic below). What we do learn is that they’re all eunuchs because their balls were cut off when they were young. We also learn that, despite his lack of balls, their leader can still feel attraction, but only towards Missandei. He never expresses any sexual interest in Daenerys (despite her running around naked a lot because she’s immune to fire and kills enemies by burning them alive and emerging naked from the ashes). And she never shows any sexual interest in him – despite his sex machine name – Grey Worm.

So let’s recap: white folks fighting white folks, white women freeing slaves, crazy violent “savages” and the most non-threatening Black guys possible. Oh, and one more thing…. All the white people have a common enemy in the white walkers, an ever increasing army of dead people led by the Night King who’s one of the most Black looking dudes in the show. The dead live outside the massive ice wall separating them from where all the white people live. (Trump must have ordered a similar wall on the Mexican border before one of his advisors told him it would melt.)

The only thing that shocked me more than how racist the mega-hit was, was how few people seemed to notice – or care. Prior to Googling “Game of Thrones racist”, I hadn’t heard about anyone calling the show racist. (When I did Google it, the first result was the Guardian story, “There are no black people on Game of Thrones’: why is fantasy TV so white?”)

Millions of people watched G.O.T. for eight years with very few having a problem with its blatant anti-Black racism. Then they saw an 8-minute video of a Black man being lynched and many of them hit the street yelling Black lives matter. What changed? The problem is, nothing.

White folks (and other non-Black folks) hit the street after George Floyd because 1) Black people hit the street first 2) Black people burned down other people’s stuff. If only one of those had happened, there would have been far fewer non-Black folks in the street.

The problem is that it’s only the most horrendous acts of anti-Black racism, followed by Black folks hitting and street and burning down other people’s stuff that gets people’s attention. Blatant racism in one’s favourite TV show doesn’t.

The riots following the acquittal of the cops who beat up Rodney King got lots of attention but that was partly because of what Black folks burned down – and why.

According to Wikipedia:

“In the year before the riots, 1991, there was growing resentment and violence between the African-American and Korean-American communities. Racial tensions had been simmering for years between these groups. In 1989, the release of Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing highlighted urban tensions between Whites, Blacks and Koreans over racism and economic inequality. Many Korean shopkeepers were sad, tired, and afraid because they routinely dealt with targeted harassment, shoplifting or theft, violence, and threats from their Black customers and neighbors. Many Blacks were angry because they felt routinely disrespected and humiliated by Korean storeowners. They still viewed the area as their neighborhood, which the Korean Americans had invaded to make a living in without learning any preexisting culture. On March 16, 1991, a year prior to the Los Angeles riots, storekeeper Soon Ja Du shot and killed Black ninth-grader Latasha Harlins. Du was convicted of voluntary manslaughter and the jury recommended the maximum sentence of 16 years, but the judge decided against prison time and sentenced Du to five years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a $500 fine instead. About 2,300 Korean-owned stores in southern California were looted or burned, making up 45 percent of all damages caused by the riot.”

The problem is not dealing with the root causes of the tension before things blow up.

COVID-19 exposed tensions created by systemic equality and contributed to George Floyd’s death being the spark that set the tinder box on fire.

The question now is, are the majority of people going to see the light, examine their role in maintaining systemic inequality, and do their part to end it – or are they going disappear into the next G.O.T. fantasy, only to emerge after the next explosion?